Solfège Wheel, Scale

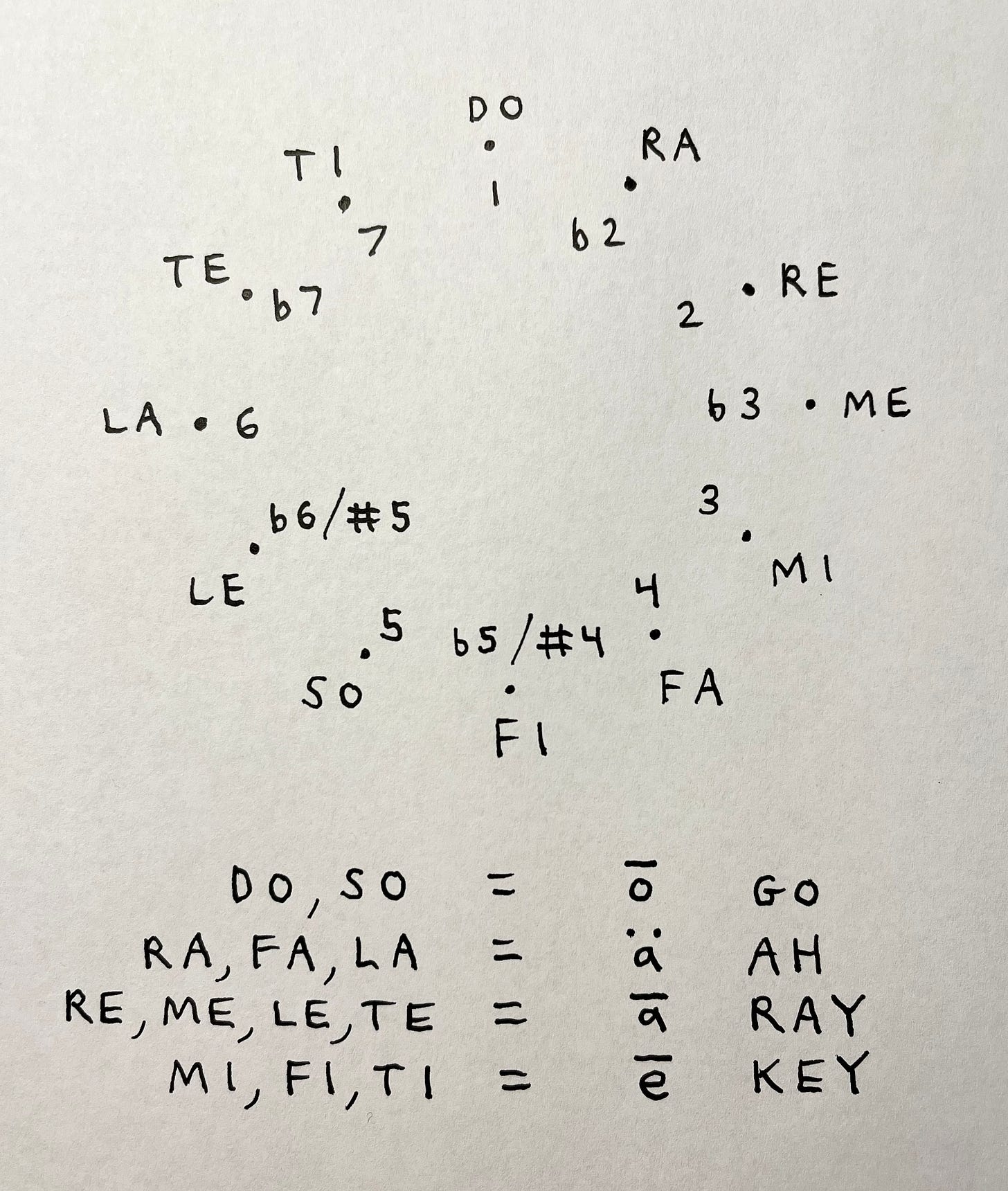

Though I still conversationally use what I’ve always called the “number system”—1, b2, 2, b3, etc. (not to be confused with the Nashville Number System, which is built atop it and designates chords in a key (and is nearly identical to using Roman numerals for the same purpose)—I’ve come to prefer solfège. I use a fully chromatic wheel:

I use moveable DO. That means I can line up DO with what I’m hearing as the tonic: the home, the context in which the other pitches are perceived. This can be a layered experience. If I’m in C major, then I’m hearing C as the DO. I call that “key solfège.” For a Dm chord in that same key, I’m hearing its root (RE in the key) as the DO of that chord. I call that “chord solfège.” None of this is pointless madness: these are names for tonal experiences of music most of us are having, whether we know it or not.

“Fixed DO,” a different system, just replaces note names with the singable, vowel-ending syllables: in fixed DO, DO always designates C, regardless of context. An advantage of fixed DO is that it does not require any analysis of how the music is functioning. A person can sight sing right off the page—they just sing FA every time there’s an F, even if the song is in F, or if they’re singing 20th-century atonal classical music (which, by definition, has no key center, rendering moveable DO impossible). Atonal music, music that is constantly shifting key, music that is tonally ambiguous—the fixed-DO person is good to go, the moveable-DO person (me!) is confused or entirely at a loss. Ironically, a significant percentage of my own music would be very difficult to convert into moveable DO.

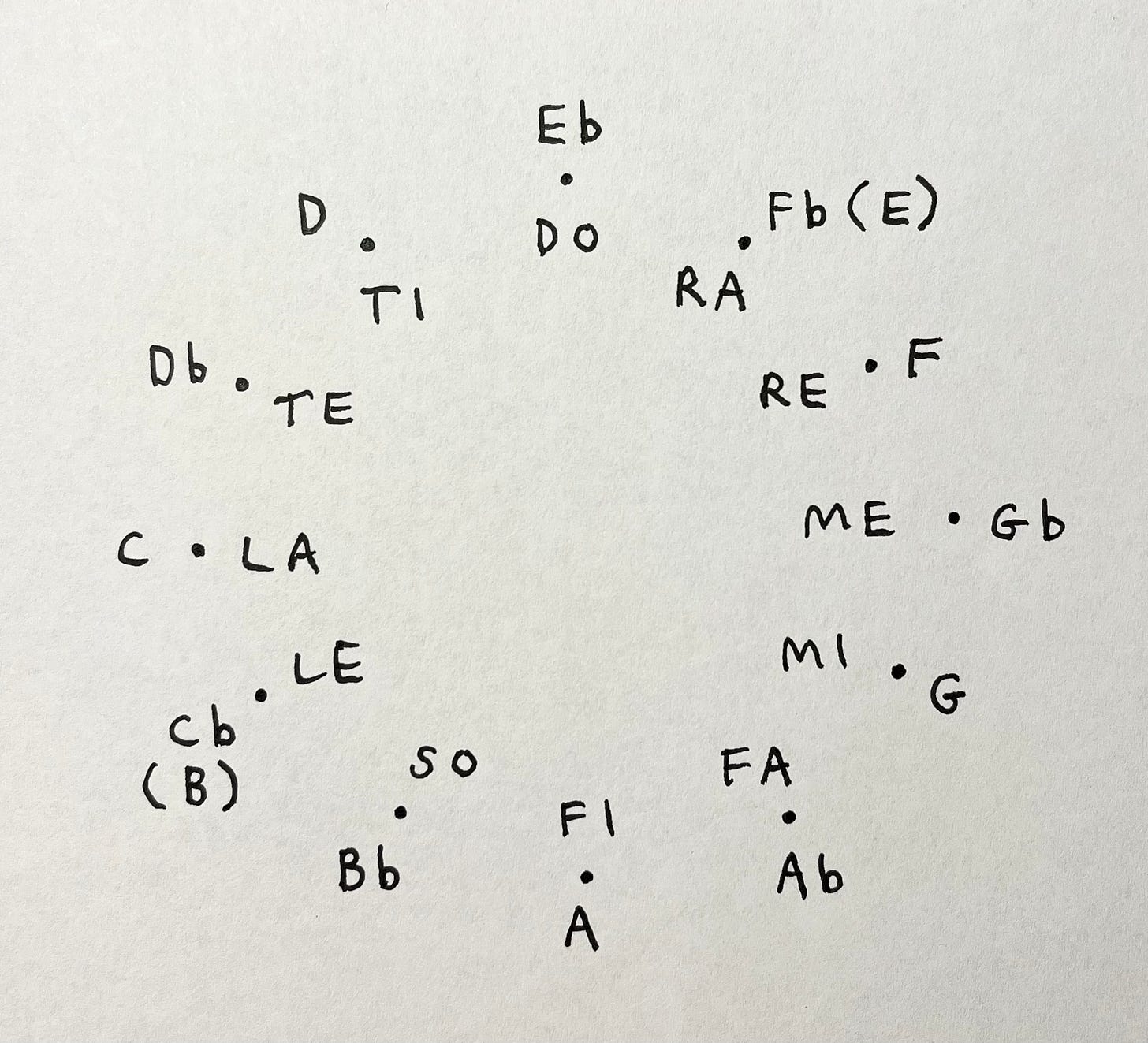

However, my primary experience of music when I’m not at an instrument is not note names, it is the tonal relationship between pitches—precisely the relationships moveable DO is built to describe and deepen. I don’t have perfect pitch. That means that until I get a reference pitch, no matter how richly and analytically I am experiencing a piece of music, I don’t know what any of the actual notes are. When it’s somebody’s birthday, once someone sings the establishing pitch and we join in, I hear the opening phrase of the melody as SO SO LA SO DO TI. Not until I ring an A440 tuning fork in my ear and I hear a FI do I know we are in Eb major and the full chromatic’s literal notes are clarified:

Everything I’ve attributed to moveable DO also applies to the number system I came up using. (There was moveable-DO sight singing in college, but the number system was my main way up until the early 2010s.) Solfège, as I use it, has two big advantages though. First, I’ve dropped the clutter of options: I strictly use only one syllable for each slot of sound, to deepen the association. A case could be made that the note a half-step above C, when it is the 3rd of a secondary-dominant A7 leading to some kind of D chord, is actually better described as a #1 than as a b2, but for me that sound is always just RA. I’ve even done away with b5 and #5. It might feel weird to describe an augmented triad as DO MI LE, but, on some level, I really don’t believe b5 and #5 exist. There are two sounds I hear as indivisible: DO and SO. They each seem to lock into something too strong to split. Everything else toggles between two shades. You’ll see that the starting letters of the syllables on my wheel align with my experience: only DO and SO start with their own letters, everything else breaks into pairs.

The other advantage of solfège over the number system is obvious: solfège is singable. The pitch itself, the context in which you’re hearing it, and the naming of the vibratory feel of that relationship all occur simultaneously. Singing the number system—e.g., “flat seven” (for a single pitch)—is a drag. You’ll occasionally hear people do it (me again), but mostly the number system is for thinking and talking, not singing. Solfège is thicker. If the goal is the deep absorption of the music materials you’re practicing, so that something below the surface becomes intrigued and begins to participate, these, in my experience, are the magic words. It’s not a guarantee—being emotionally electrified by something seems to be the most important thing—but solmization brings me into that state: buzzing, open, expansive.

When you’ve gotten something properly down there, you see little warped fun-house versions of it pop up in your writing and improvising (if you recognize it at all), sometimes years later, often uncannily bending to the breeze of the total music, freely modified (by who?) to blend into the magic at hand. Conversely, poorly digested ideas can only be consciously pasted to the surface of your music at the expense of an organic whole, unintegrated into their surroundings.

And this brings me back to the headache of applying moveable DO to a nontrivial amount of my own music. The thing is: I don’t. For me, practice and solfège are for the slow, patient introduction of new ideas (or new perspectives on old ones (always possible!)), presented to myself as clearly as possible. The way I’m trying to hear a given set of pitches may be difficult—often it’s another DO that’s used to being in charge trying to wrest away control (like when a person is first trying to hear C lydian and they keep realizing they’re back in G major again)—but I definitely know what I’m going for, what I’m trying to expand my worldview in order to experience. Once the deeper place takes hold though, all bets are off. The world of naming and clear meaning are strictly a front-end business. Analysis of the finished product may be fun and instructive, but if it’s worth its salt, any music, even “my” own, will overpour with mystery, questions. It’s the work of fairies, a nonhuman intelligence. We are collaborators at best. And a good collaborator sings that sweet solfège!

Here’s a scale I’ve been exploring:

Because I’m insisting that the D is the DO, the DO is standing on one leg, as it were. Something to look for is whether a given DO has what I call “SO support.” SO is a powerful ally for a DO and can help it hold that position. (Remember, a particular note being DO is not merely saying that it is; you have to teach your ear to believe it—music is like the vase/face of Op art or like Magic Eye: these are real shifts.) SO is the lowest, most audible non-DO overtone of DO, and having that ally reified outside of DO as another pitch can help to strengthen (this particular) DO’s position as the (temporary) ground of our experience of all pitches. Our DO, here, doesn’t have it.

The first thing to memorize (rather than have to calculate) is all 12 DOs’ respective SOs. They are near the midpoint and will help a lot in filling in the full spectrum—knowing right away, e.g., that if DO is F, LE is Db. Skimming over the scale, I can see which of the other scale degrees would have “SO support” if they were made DO. Eb has its Bb. F# has its C#. G# has its Eb (you have to see past a weird spelling here). Bb lacks its F. C# has its G#.

I recently came across a name, online in a Serialism-forward index of all possible scales, for these scale degrees without their own SO present: “imperfections.” D and Bb are the imperfections in this pitch collection. In C major (or any of its modes), B is the one imperfection. So the DO of my new scale is an imperfection, with all but one of the other scale degrees equipped with support our D can only wish for (or hope to imply)—it just makes me fight harder for my friend!

The first thing to do is practice singing the scale, up and down, whatever range you can comfortably manage, and then improvising with it, all with the solfège, over a drone: just the D. The chromatic cluster around the DO is the easy part, the sea-sick SO-less middle is more difficult.

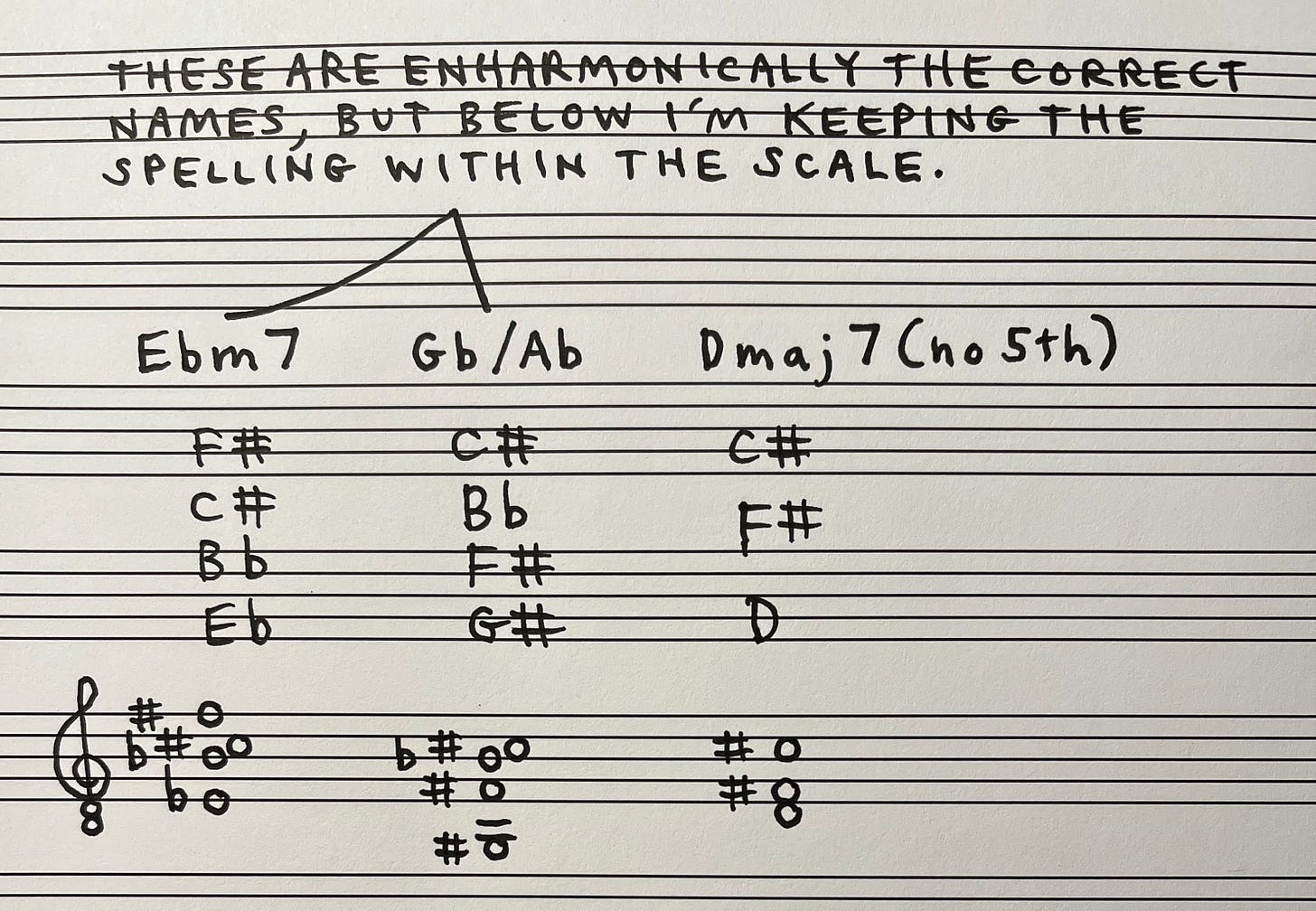

I like taking a scale like this and mismatching it with the kind of cadential thinking associated with the major-minor system. I was examining what I might get away with with the materials at hand—could I suggest a V chord though I had no SO?—when I made an odd discovery: the scale contains a typical ii V, with one of those 70s-sounding Vsus9s I love so much, but… the whole thing is sunken down a half-step!

The difficulty, though, is actually hearing this in D, and not just having the ii V pulling you down into Db right away. With no establishment of D as DO beforehand, I am nearly hopeless. The Dmaj7, with no SO technically (though it’d be lovely if the ear would fill in the missing pitch), just sounds like a tritone sub-esque prolonging of V: I keep expecting it to drop a half-step and cadence in Db.

So—and I leave you with this for the week—I wrote something to try to help our imperfection, and its weird sunken ii V, have their moment in the moonlight, all fleetingly heard in D. And I hope it sinks down into our dreams and messes up our music nicely for years to come.