Inverted Tuning

1) replace the low-E string with a high-E string

2) replace the A string with a B string tuned down a whole-step to A

3) regular D, same as standard

4) regular G, same as standard

5) replace the B string with a D string tuned down a minor 3rd to B (putting it a whole-step above a regular A string)

6) replace the high-E string with a low-E string

Ella Feingold, a new friend, is making Inverted Tuning, a tuning I invented in 2008, suddenly something people have heard of. Recent years have been like a bouquet of unlikely, wonderful turns for me, and this is certainly one of them. Not only has an incredible musician made Inverted her primary tuning, but she’s popularizing it. People are going to the trouble to restring and modify guitars to try it, and getting their minds blown like I did fifteen years ago.

It was an ember that was burning pretty low. Though albums of mine with the tuning still circulated—(some) albums from 2008 through 2011—almost nobody knew what they were hearing. The tuning wasn’t used exclusively, was often mixed in with standard-tuned guitars, and I never wrote what any of the instruments were in the liner notes.

I’d gotten caught up in other things, swept away to other places (places I’ll tell you about, here, soon enough). I’m nearly certain there is zero Inverted Tuning on any of my albums after 2011.

When I went to Los Angeles to record with Blake Mills at Sound City in 2022, though—working on an album of his called Jelly Road that we co-wrote and co-produced together—I made sure to show him the tuning. It’s a cliché to say stuff like this about him, but Blake is one of the most inventive and gifted guitar players I’ve ever met, and I had to see what he’d do with this octave-scrambling, mind-scrambling novelty. We went over to Old Style and picked up a decent nylon-string* and some strings, and while Blake and Joseph Lorge worked on something in the control room, I Inverted it in Studio A (still not at all over the fact that I was alone again in the room that Nirvana recorded “Smells Like Teen Spirit”—lights low, an uncanny, confectionary significance to, seemingly, the physical air).

*Nylon-string guitars have always been my favorite—I started on one—but it wasn’t until Inverted Tuning had been around for a minute that someone told me something strange about them: all the strings on them are (almost) exactly the same width. This means that the nut doesn’t need to be changed to Invert one. All you have to do is restring it—the slot for the low-E string is the same size as the slot for the high-E string. I.e. if you want to try this tuning, it’s easiest to try it first on a nylon-string. If you fall in love, you can fuss with modifying electrics, buying a lefty (or a righty if you’re a lefty), etc. I know Ella has worked out some string-gauge and set-up details for an electric. She’s the one to reach out to for that stuff.

Inverted Tuning is on Jelly Road—Reuben Cox even built us an Inverted electric rubber-bridge guitar while I was there (the videos in my phone of Blake playing it for the first time are insane)—but sparingly. Like on Living With Poison, HI, Transparency, and Message From Work, it was a tool among many.

I’ve known since 2008 that the tuning was a gold mine, but I also knew that its riches weren’t necessarily mostly for me. It wasn’t disinterest that led me away from it—I’d barely begun to scratch the surface—more just a feeling that it was here in the world now, there was no rush.

I’ve heard stories about Blake handing the Inverted nylon-string to guitarists when they visit Sound City, and—as you’ve heard if you’ve followed Ella’s story with the tuning—it was when Blake saw that she’d been experimenting with playing a lefty guitar right-handed (not mirroring Jimi Hendrix, not restringing it for the new orientation) that he reached out to tell her about my tuning. (What I didn’t realize until texting with Ella while writing this: Blake told her about it on 6/6/22, when I was still in LA with him, five days before I flew back to Vermont.)

Ella’s story with the tuning is her’s to tell. But here’s my story of how I made it up:

I was thinking about Elizabeth Cotten. She was a lefty playing a right-handed guitar, and like Ella was experimenting with before Blake showed her Inverted, not restringing it. This meant her high strings were high (in the air) and her low strings were low (to the ground), the opposite from normal. I was wondering: could I have the strings like that, but have the pitches not be flipped upside down?

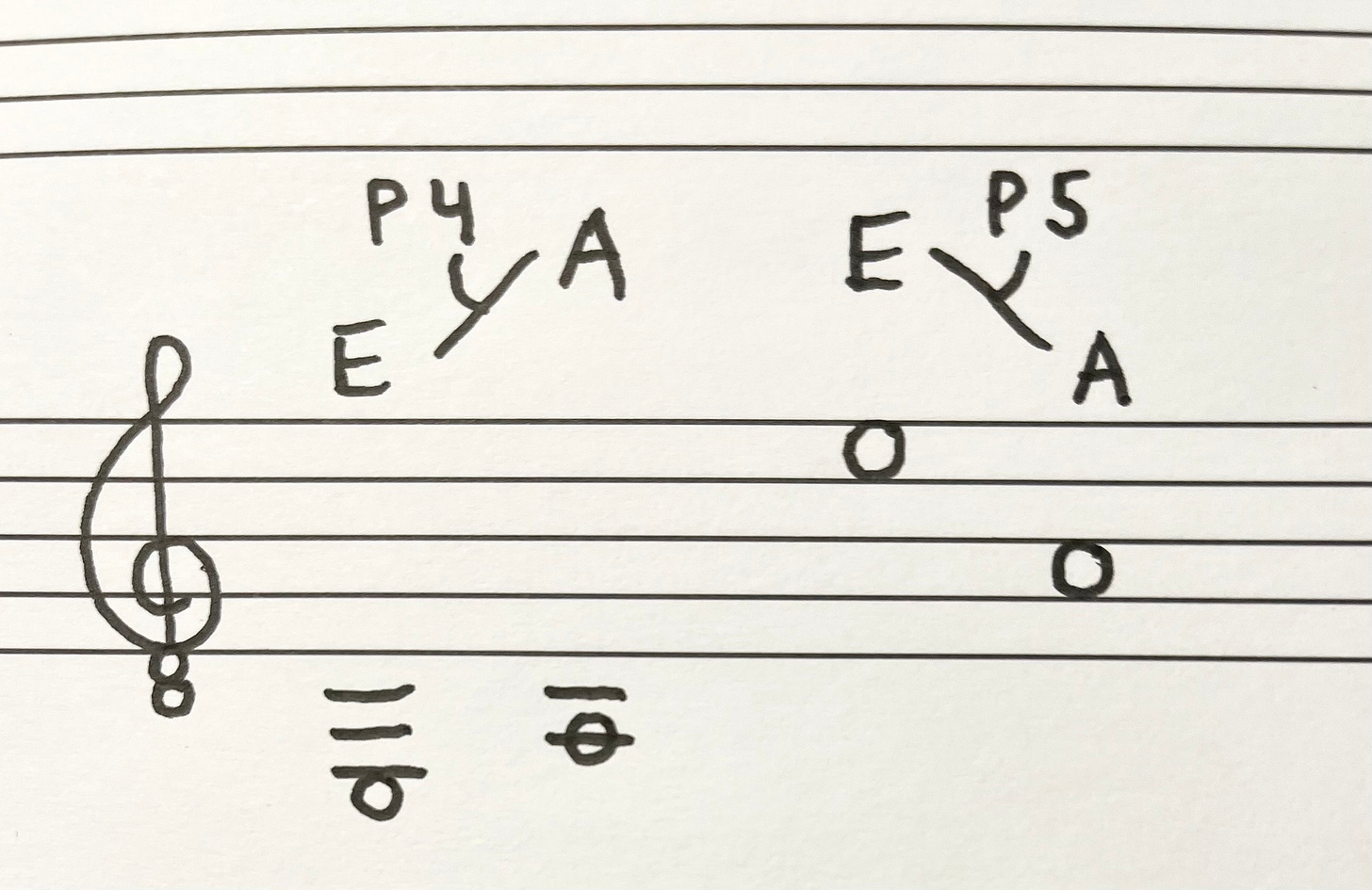

This led me to interval inversion, the inversion “Inverted” refers to. Let’s imagine down from a high-E string strung where the low-E normally goes. So instead of the low-E going up a perfect 4th (5 half-steps) to an A, the high-E in that spot is going to go down a perfect 5th (7 half-steps) to an A:

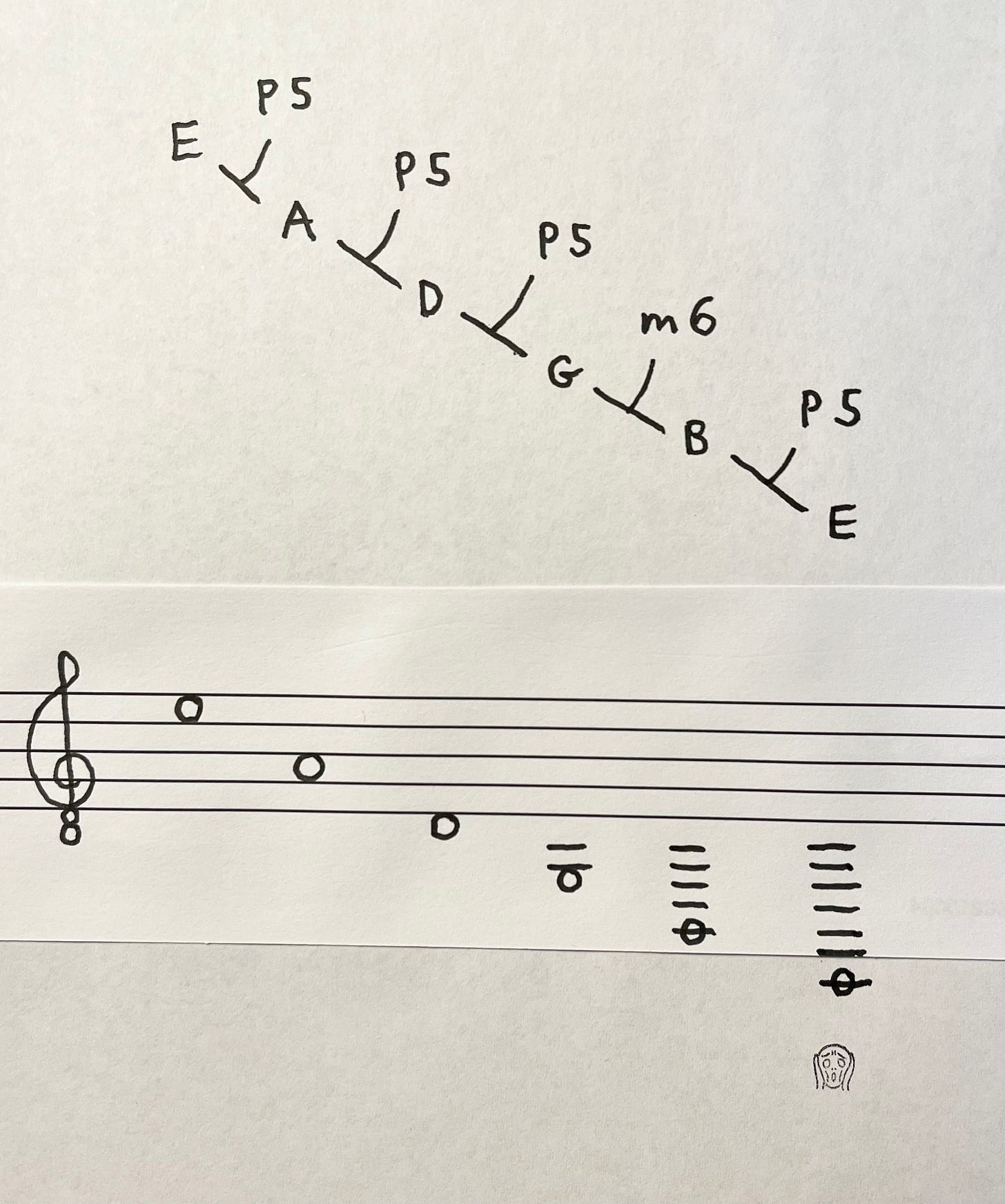

If you follow the logic of this all the way through, you get this:

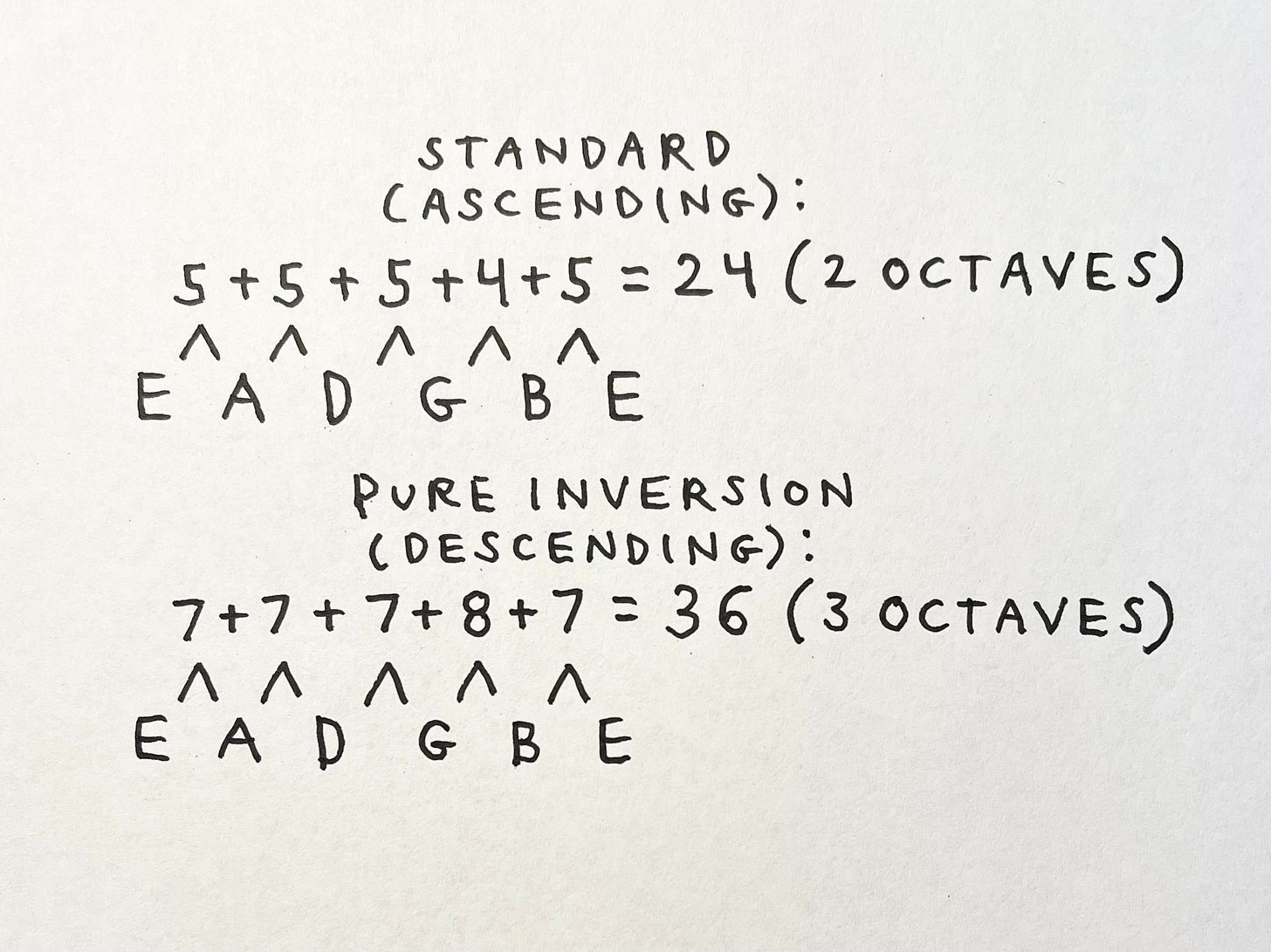

Because the perfect 4ths are inverting into the larger perfect 5ths, and the major 3rd (4 half-steps) between G and B is inverting into the twice-as-large minor 6th (8 half-steps), the ground covered from the highest string to the lowest ends up being an entire octave more than in standard tuning: you’d start with a high-E up high and end up with an E string from a bass down low. I.e. you’d have to build a whole new instrument to accommodate this range of tension. Chords would become mud. Here’s the math, in half-steps:

So here’s where I got lucky. Instead of just saying, “Oh, this doesn’t work,” I allowed for an impurity. I knew I wanted to end up on a guitar low-E at the bottom, not a bass string. And I was still attached to not having to think about the pitches on the neck upside down—I knew I wanted only the octaves of the pitches messed with, never the pitch classes themselves. So I just raised the low three strings an octave. In the dead center of the concept, I basically pulled up the plane so it wouldn’t crash, so it would land where I wanted, and resumed the idea. I was intrigued to see that the middle two strings ended up exactly where they normally are in standard, a D going up to a G—one ascent, one move against the grain. I had “Inverted Tuning.”

But I hadn’t heard it yet. I lived in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, then, a few towns over from where I’d grown up (I’d ended up back in the area after a relationship ended). Gary’s Guitars, a small but magical store people in the region adore, was literally a five-minute walk from the school where I taught, and I walked over on a break, carrying my cheap Telecaster copy I’d recently picked up at Gary’s. Gary, an open minded and relaxed guy, was interested, willing to humor me. He’d have to flip the nut around. He’d call me in a few days.

I haven’t made it back to Gary’s in a long time—I moved to Vermont later that year—but I called while writing this. Gary sold the business to his employee Marc, who’d been with him for twenty years, in 2019, but it’s a soft retirement: Gary still works on guitars in the back a couple days a week. The person who picked up the phone when I called had no idea who I was (I didn’t expect them to), but, shockingly, they did know about Inverted Tuning, “from Ella Feingold’s Instagram.” They just didn’t know they were standing exactly in the room, at the back of the Hannafords lot down Islington, where it was from! Gary happened to be there working, and it was a pleasure to talk to him. Long live Gary’s Guitars!

When Gary was done Inverting the Tele copy, I went and picked it up. It seemed like this idea was actually gonna work, and Gary seemed to think so too. Back in my lesson room at the school, with the guitar plugged in, my head exploded. First of all, though 4ths and 5ths both may be “perfect,” a perfect 5th is a world away from a perfect 4th in terms of consonant buzz: the three open 5ths between open strings had this under-$200 instrument veritably levitating with resonance.

And here’s a metaphor for you: it was the “impurity” in the tuning, the compromise I’d made, that was the tuning’s greatest gift. The A and G strings were only a whole-step apart. D and B were only a minor 3rd. Close voicings normally impossible (or, at best, requiring clever work-arounds or horrible stretches)—exactly the rich, close harmony I gravitated to on a keyboard—these voicings were suddenly… easy. Reality shifted. It was springtime.

To be continued…