CW96

One thing I found myself doing on Lightly, my most recent album, was modulating down a half-step.

A truck-driver modulation pushes the music, usually a late-in-the-song repeat of the chorus, up a half-step or whole-step, with or without preparation. I’ve always loved these modulations, used them, pushed what I can do with them.

Just yesterday I was writing some two-part counterpoint on paper and, mid-phrase, I heard the music two bars back wanting to repeat, but up a half-step. There was no preparation; it was just as if that measure had sucked in a little helium for a lift. (In a sense, it created a problem, but in another sense, dealing with it found the phrase an interesting way forward.)

And a lift is what a truck-driver modulation gives the music. So shouldn’t modulating down be… a downer? It hasn’t been feeling that way. The half-step-down modulation feels rich, wide, even inevitable.

And you could argue it is more inevitable than modulating a half-step up. If you’ve been in, say, G major, and then you modulate down to Gb major, you could think of G as a long tritone sub of Db: as a dominant waiting to resolve to the lower buzz of the true tonic.

If the music had gone up to Ab major instead, you could argue that the G triad was made from chromatic lower neighbors to the Ab. And, particularly in jazz and country music, you will see a G as a sub for an Eb7, and then the whole thing bends up to Ab. But, at least to a degree—almost as if literal gravity were somehow a factor—I like to think (at least while making this argument) G would prefer going down to Gb over going up to Ab.

All this, of course, is just for fun. Anything can happen, can become a convention. You like the effect of something and then you build a theoretical argument for it. I guess this is obvious, but I don’t think this secondary game is any less pure than the initial game of moving notes around and feeling things. It’s all one playground to me—wild ideas and rides and emotions. It’s fun to turn things on their head, and then it’s fun to think up a reason (besides just the joy of contrarian variety) why it works so well.

And that theoretical story—no matter how lightly you take it—can be like a voice on your shoulder urging you forward into your curiosity. It’s like: all the status quo stuff around music (which extends into all the business and marketing and everything) has all these specious arguments holding it up, so why shouldn’t you have them too when you break formation, when you split off from the same old? I can report: when I found myself doing wrong-way semitone truck-drivers, my comic tritone sub concept—which occurred to me while making the album—was like a lavender perfume or a friendly pink cloud filling my sails just that little bit more.

I believe I am not alone in my favorite thing about the movie Help! being the apartment the Beatles live in. It looks like they’re entering four separate terraced houses, but then the houses are connected inside; the shared walls have been removed and it’s all one place.

My point, though, is John’s bed. It’s built down below the level of the floor. The image came to me when thinking about the semitone downshift. Most days resolve when a person climbs a level up onto their bed. John’s bed says, “Let me take you down.” I’ve always loved that bed.

Here are the places the idea shows up on Lightly. I’ll see if I can find them all.

“I Just Don’t Want To Enter Your System” (Track 1):

The whole song, while colorfully so, is in E up until the surprise ending. The melody is holding a D# over a B7 and then out over the final chord. But instead of cadencing on, say, an Emaj7, a chord the song is already familiar with, we get an Ebsus2/G. TI resolves to DO by becoming it.

“Not Even Close” (Track 3):

The intro is in Eb, though it ends on a weird detour to G(2). But then the A section, unflinching, is in Eb. It ends on an Ab/Bb, a clear V, but then drops for the repeat: the whole second A is in D. (You could argue the G(2), which does seem to function as a sinking of the IV chord that precedes it, foreshadows the move to D.)

The second A ends on G/A. It hops back up to Eb to begin the bridge, but the Eb has a D under it. We get to feel both a return to the original key and, in the bass, a quick sensation of V to I in D, of staying where we went. Both are illusions: the Eb is a IV chord and we’re actually in Bb. Then everything is sliding around. Let’s not get caught up in it beyond saying the music winds up, at the end of the bridge, on G(2) again.

Then we get an A section in Eb, plus a tag (maintaining the key), another intro (now outro) ending on the subdominant-of-D? G(2), and some birds out the window.

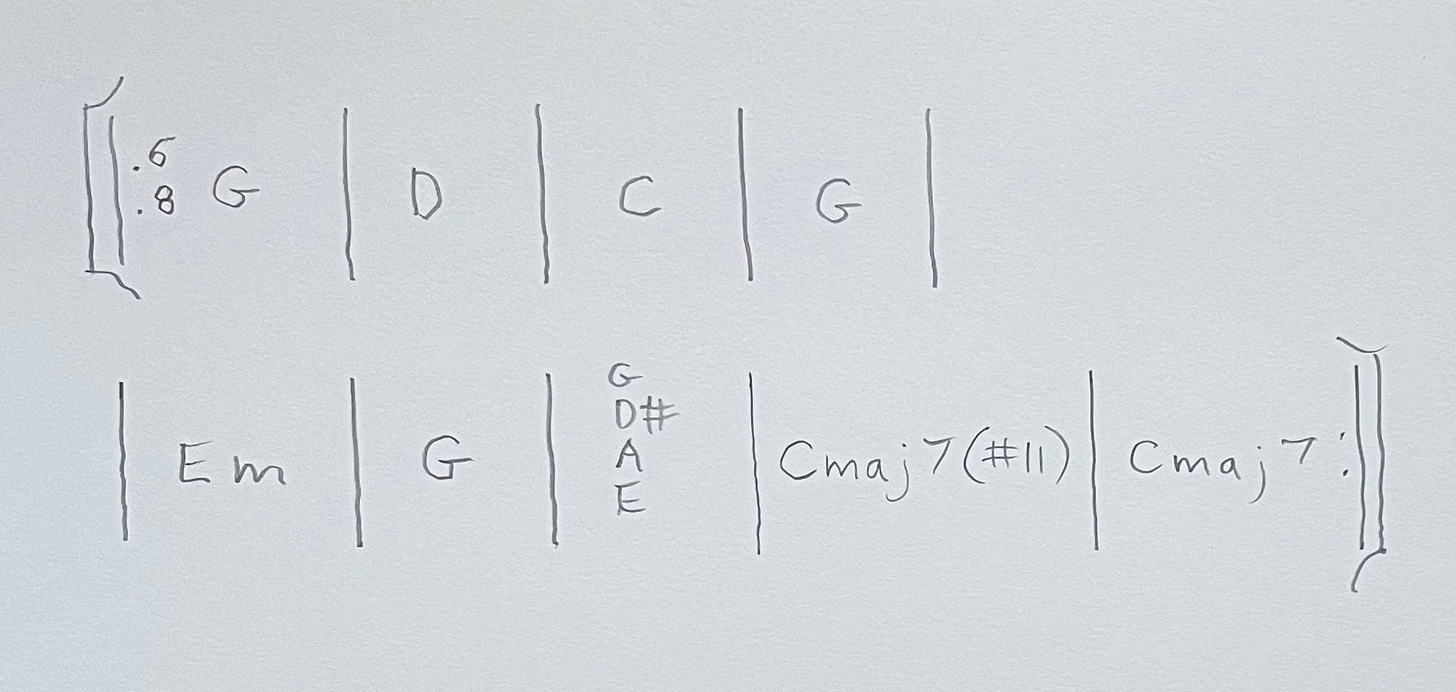

“Believe Blue Notebook” (Track 4): A one-section song in G with an odd number of bars and one interesting chord.

(The interesting chord, which I just represented with a pitch stack of the voicing, can be called E minor major seven with a 4, but no 5. It’s an AIT, the third mode of A Open Darkness.)

The last time, though, it does this:

The melody is an F# over the D chord, and then that note, over Gb, becomes DO. It’s the same ending, basically, as “I Just Don’t Want To Enter Your System.”

(The next track, “Lightly,” begins in the new key of Gb. Because I wrote this album in order—something I almost always do—I could do this on purpose. “Lightly” is eventful, but it’s in Gb the whole time—a brief dip to F (see below) excepted—to my ear. It moves through a G a few times—G(#4), Gsus2/B—but they are plainly bII chords: exactly what my funny theory suggests every G from the beginning of “Believe Blue Notebook” really was.)

“Lightly” (Track 5):

In the midst of a bridge with wordless singing, the music drops from Gb major to F major. It happens, melodically and harmonically, a cool way, and the return to Gb is, if I say so myself, very pretty. That whole bejeweled ending of the bridge is my favorite part of the song.

“The Galleries” (Track 6):

This song is in Db, and while it does move from a Db to a Csus4 to C right away, no modulation has occurred. The C seems to function something like the tritone sub of the IV that follows it.

I will say: even though major chords dropping by half-step—like Syd Barrett’s Pink Floyd, John Lennon, etc.—isn’t the sink-down truck-driver modulation I’m writing about today, they do remind me of each other. I clocked, while writing, that getting to that C chord fit the broader theme. What is a key change and what is a tonicization and what is just a chord change is an interesting subject. Clear distinctions and unclear ambiguities both arise. But in the heat of writing it can all get a little: [Nigel Tufnel pause] “These go down one more.”

“What You Should Do” (Track 7):

This song has major triads going G to G# to A in the key of D. This isn’t modulation, and isn’t descending, but I still thought of it as related when I chose that G# chord like I was a caveman that couldn’t think of any other options. (I was also a caveman when I kept playing the same A major pentatonic notes (the only ones it has) on that little pitched flying-saucer-looking percussion instrument, when I didn’t lay out on the G# chord or try to hit it better. It sounded fine!)

“The Earth Took Form” (Track 9):

Key of C. A D/A down to C#/G# (tonicizing F#m) in the B sections, but that’s it.

“Spiral Out Of Control” (Track 12):

Key of G. An Eb to D to Db (major triads with some 6/9 coloration) twice in the bridge, but that’s it.

I count four legit modulations down a half-step (two that stay there, two that come back up). That’s one for each terraced house. We can share them inside. 💕