CW94

There’s a musical detail of “Cymbal” that I’d never noticed before, until writing last week’s post.

I remember writing the song in the room I shared with my brother, him across the room tolerating* my stops and starts while I tried different chords under the melody.

*He used to do a funny imitation of me writing back then. Hearing it from the outside was comically crazy-making. It sounded sort of like a robot breaking.

In my mind I was writing something like a John Lennon song from the White Album, something with that late-Beatles “classical music” feeling.

More specifically, I was using second-inversion chords in a John Lennon way (e.g., “Julia”): as if the bass note just didn’t really matter to me. I was, with a sort of irony, using voicings I’d learned to play before I could do full barre chords. (I still really love that feeling. I’m so completely focused on the outer voices—in that sense I’m more like Paul—that it’s kind of dreamy to flip the coin over and go bass-blind. (I recently bought a bamboo baritone ukulele—just the top four strings of a guitar—and it’s really fun to play it that way.))

None of this yet, though, is the musical detail I hadn’t noticed till this summer.

Before we begin, I just—one day before publishing this—realized that the recording is pitch controlled: the guitars are slowed down on the 4-track so the singer can sing over the song in a lower key. I know for sure “Cymbal” was written in Bm (moving to D), and I can hear the guitars are voiced that way. (And I can hear that the voices—there’s that one line of backing vocals too—aren’t slowed down. (The melodic guitars? the bass? Ben’s solo? I can’t tell.)) The song is oddly dropped—I know this wasn’t on purpose—to about 50 cents sharp of the key of Am (moving to C), while “Strawberry Fields Forever” begins about 50 cents sharp of the key of A. I.e., you could cut* the “Cymbal” intro in right as Paul’s Mellotron intro—which at first seems to be in E—drops you in A for John’s vocal entrance and it would work. The fact that the telltale lethargy, both of pitch and tempo, of the “Cymbal” recording had not alerted me in the intervening years to this forgotten decision just goes to show the power of “knowing” something: that the song was in Bm when it really wasn’t. In any case, I will be discussing the song in the key it was written in.

*If we could cut. A couple hours ago when I was sleeping, I was dreaming about a recording with Syd Barrett’s voice at the beginning saying “Cuttage.” I was using a DAW on this iPhone that I’m working on right now—I’ve recorded on an iPad mini since 2019 but I only use Voice Memos for music on this phone—and I heard the word several times while working on the track. Then I accidentally muted it but I could still sort of hear it. Cuttage. Is this dream a precognitive intimation of the ready-to-go “Strawberry Fields Forever”/“Cymbal” splice I would discover a few hours later? If you are intrigued (rather than annoyed) by this subject, I recommend Eric Wargo’s 2024 book From Nowhere: Artists, Writers, and the Precognitive Imagination.

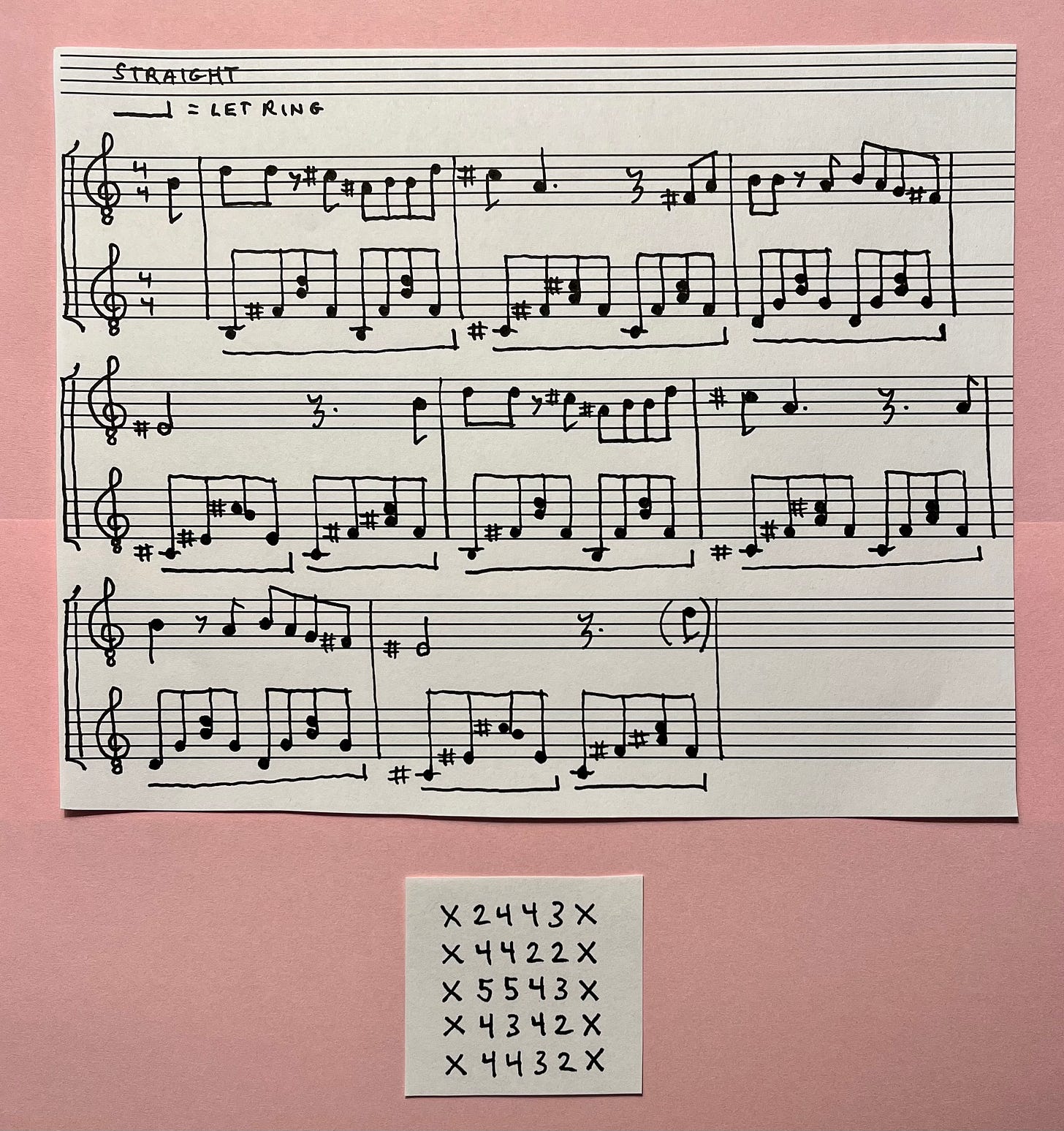

The intro puts a low descant (on a very out-of-tune fretless bass (that’s me, not Ben)) “over” the opening chords—the G on the C#7(no 5) is a nice touch—but when the singing comes in, the bass drops out and we have this:

Later on parts are added, including the return of the bass descant, but this is the basic verse.

Most striking, at least to my ears now, is the way the melody ends twice on an unresolved FI (key solfège). Yes, the resolution to the SO a half-step up does technically appear in the chord that follows, but I don’t think it works that way.* The protagonist leaves us hanging.

*Usually. I did hear, at a performance at an art opening at a lily farm on Saturday, my friend Omeed throw the final note of a melody from his voice onto his guitar. It was not merely the presence of that note in a chord though. He breathed the melody over to the guitar, threw his voice there—it was more like a magic trick.

The melody of the pre-chorus begins, after a little D pickup, on the F# we’ve been waiting for—and even, after a little swing up to G, stays there when the chord moves to Am*—but it’s not really the F# we’ve been waiting for. It’s an octave too high. Resolving up a half-step and up a minor 9th are not the same.

*This is very 1968 John Lennon. Both the insistent melody note while the harmony shifts its meaning from below, and the m6 chord sonority.

So first I woke up to the idea that the central tension of the song is that unresolved FI.

And then I realized Ben begins his guitar solo by resolving that tension. He gives you a big FI to SO, precisely what you’ve been waiting for, whether you were conscious of it or not. It’s in a different part of the form, and it happens an octave up, but finally a FI is explicitly resolved up by half-step to SO.

(On the downbeat where Ben, after two FI pickups, bends the FI to SO, the vocal melody below Ben’s guitar drops a half-step: a held D (over a C/G) resolves to a C# (over Bm). Contrary motion in half-steps. So the opening notes of Ben’s solo work like clockwork with the song that way too.)

Ben may well have had a high-level view of “Cymbal” that I did not and known exactly what he was doing. I only noticed that the entire song finally releases—like rain clouds finally opening up on us out in a field at Tuttle’s—in this spot. Now I see another reason why. 💕