CW92

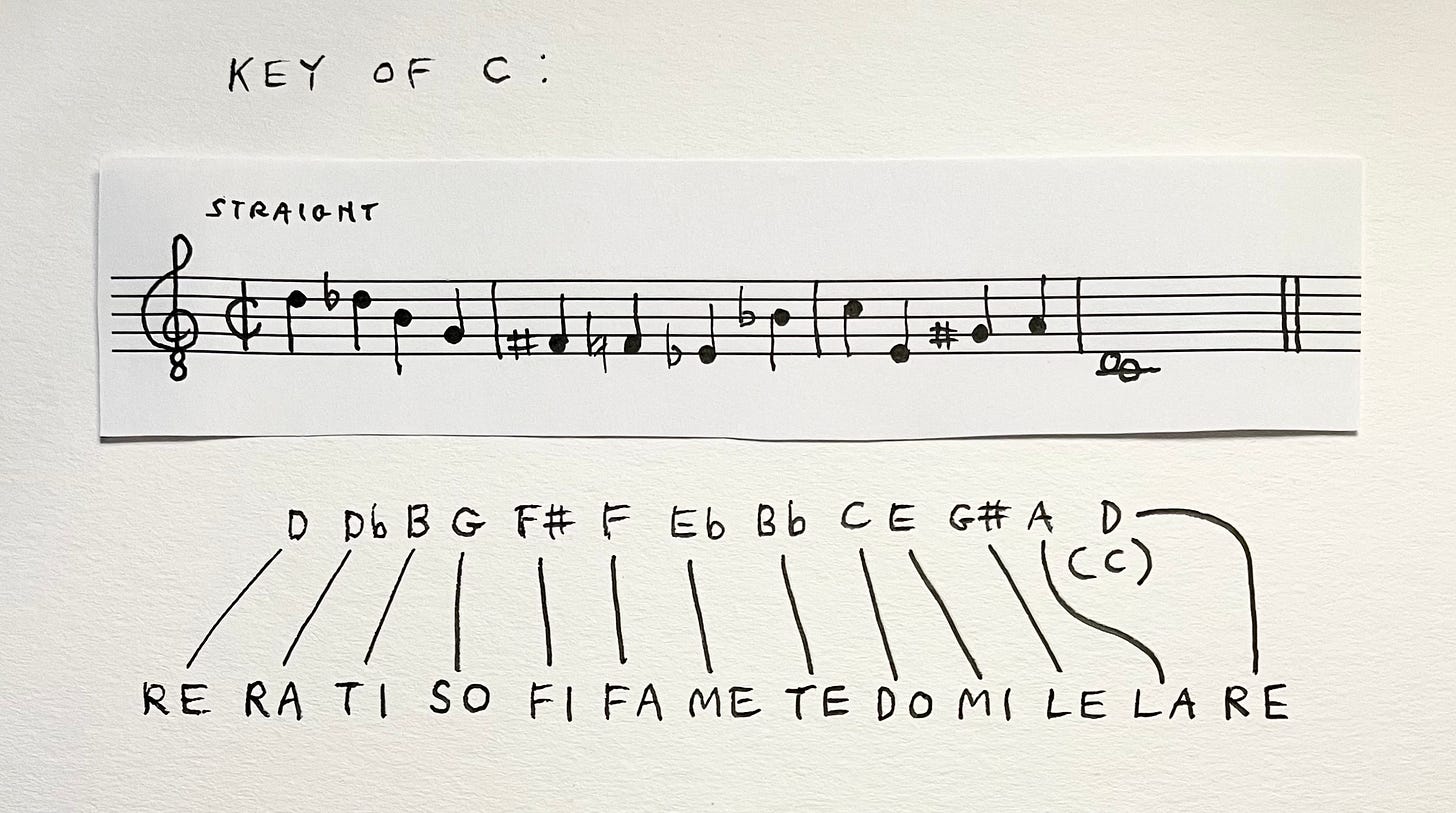

About ten years ago I thought up this idea I called a “tonal row.” I had this one that I used to sing over and over while hiking Mount Wantastiquet, but I can’t remember it. Maybe it’s in a notebook somewhere. There were a few other ones over the years too which I also can’t remember. I made up a new one for today.

Here’s the idea:

Tone rows are the main building block of the twelve-tone technique, developed by Arnold Schoenberg in 1923 (though he was beat to the idea by a few years, apparently, by a composer named Josef Matthias Hauer), and used by serial composers who followed in his footsteps.

The basic idea of the tone row is simple: before you’re allowed to repeat a pitch class, you first have to hear from the other eleven. The goal is atonality, the avoidance of a key center. Something like: if twelve people all get to talk exactly the same amount, it will be much more difficult for one of them to take power.

Once you’ve ordered the pitch classes into a tone row, it can be messed with in various ways (transposition, interval inversion, retrograde (playing it backwards), etc.—it gets (very) complex), but the row—with its goal of keeping tonality at bay—is primary.

My idea of a “tonal row” is almost a joke. Can you construct a tone row with the exact opposite goal? So that everything is obviously oriented around an unambiguous key center? The answer is yes. It’s not that hard.

If you’ve spent any time studying and improvising bebop, you’re well on your way. Bebop is a highly chromatic music that is also totally tonal. You could argue that the goal of atonal chromaticism—though this is not a very warm description—is keeping you disoriented. (More generous: waking you up to a state of being, redolent of Zen Buddhism, outside the hierarchical hearing of tonality. Schoenberg’s student John Cage, though he meant something more radical, describes atonality nicely with “everywhere is the best seat.”) Conversely, the chromaticism of bebop is all about masterfully approaching the phrase’s tonal goal in a wonderfully slippery and agile way.

Putting together a tonal row is similar to constructing a line of bebop, albeit not in real time.

A good test for making sure you really are hearing your row in a single key—and not just saying you are—is being able to sing it in solfège without the support of an instrument. (I’m speaking to those of us, myself included, without perfect pitch, of course.) If you’ve constructed it well, you should be able to lean against the walls of the key, as it were, without drifting or getting lost. It shouldn’t feel as difficult as singing a tone row, even though it is one.

Here’s the tonal row I wrote for today: