CW68

Today’s post involves what I’ve been calling the gospel scale, a major scale with no 7, but I’m not gonna call it that anymore.

The internet mostly agrees—including actual gospel musicians, which I am not—that “the gospel scale” isn’t what I’ve been saying, but is instead the second mode of the blues scale: DO RE ME MI SO LA, a major pentatonic with an added b3.

I’ve been using this mode since high school, and to add to the confusion, when I used to teach it to students—I have been on a break from teaching, with a few brief exceptions, five years next month—I sometimes called it “the country scale,” because it sounded like country music to me.

What I’ve been calling the gospel scale is the I and ii triads combined (or alternating) that Jacob Collier talks about as a gospel sound—that’s where I heard about this thing that, yes, does happen in gospel music (a lot does!).

Misunderstandings can lead cool places, but there aren’t any actual music mistakes here. I was just using a confusing name. It’s like I was going around calling something I was excited about that happens in blues “the blues scale” that wasn’t the blues scale everybody else was talking about.

I just rewatched the beginning of Pablo Held’s video of me explaining my new major and new minor scales, both built using my “gospel scale.” Right away at the beginning I say “major minus 7” and Pablo has to clarify that “minus 7” means “no 7.” Given that a minus symbol can mean minor (in chord naming), it is a little confusing. (Like, could I possibly be describing mixolydian a novel, insane way?) So do I call what I was calling the gospel scale “major minus 7,” “major no 7”? Should I always use solfège and say “TI”?

A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds. As always, I will aspire to clarity, but I don’t want to go too crazy. It’s better not to tighten up the shop too much. The life-changing magic of not tidying up. 🦋

The jewel of the major scale with no 7 is set cleverly (if I say so myself) two ways for new major and new minor—see CW15 for the details.

But I’ve just been practicing it straight-up, as DO RE MI FA SO LA. It never ceases to impress me how the erasure of one note can change so much, can give you all this new stuff to practice, all these lovely surprises.

I was pushing a dyad up through the scale (key of Ab) and I was surprised to find myself disturbed by some parallel 5ths.

I’ve mentioned the theory and ear training classes I took at UNH before, in CW30.

When I was at UNH, from 1995-1999, my favorite professor was Michael Annicchiarico, a composer. (He’s still there. 💕) I studied theory and ear training with him—a beautifully-designed interlocking whole, beginning with species counterpoint in the fall of 95, and finally arriving at the Tristan chord in the spring of 97, at the foothills of the “emancipation of the dissonance.”

Species counterpoint had all sorts of interesting rules we had to follow. But me and my friends also loved Romantic era Western classical (particularly the French composers), plus the whole bouquet of twentieth-century popular musics, all of which flagrantly disregarded many of those rules. We were not native to this bygone way. (However much the music we more readily related to owed to it.) So, for one example among many, though we were avoiding parallel 5ths in our counterpoint exercises, we definitely couldn’t hear anything fundamentally wrong with them.

That is, until we really got down into the magnetic principles of the world we were investigating, the context we were in, the puzzle we were trying to do.

One thing you can still hear people say—though it was especially prevalent in the punk-pilled indie rock aesthetics of that era—is that if you “learn music theory” it will take away your creativity, snuff your tremulous candle. I’m sorry—I can hear my own distain—I just really disagree with that. I always hated what I thought of as the enforced illiteracy touted as superior in certain circles.

It’s not that I don’t love “untrained” musicians, it’s that I don’t only. There are endless kinds of music, and as many ways to engage with them as there are individuals. I’m not going to pretend there’s no difference between John Coltrane and the Shaggs, but I do think it’s a lot more complex than the tired “classically trained”-versus-“by ear” binary. (Coltrane and the Shaggs both practiced a lot—just saying!)

I don’t believe “you have to learn the rules to break them.” But I also don’t believe studying music will crush you.* Rules, to me, are just games. In my experience—as a student, and in my decades as a teacher—those games just make us sharper, more flexible, more expressive. More ourselves. You take what you need, leave the rest.

*I do believe a bad teacher can really mess a person up. But that teacher could be anybody with whatever amount of whatever kind of training. Anybody who tries to make themself feel better by making other people feel small, lacking, that something is wrong with them. (Many bad teachers have serious gaps in their knowledge and abilities and are cruel as a kind of compensation. Others are terrific at what they do, but have a highly circumscribed sense of what counts and what does not.) A good teacher knows everybody has something beautiful to offer and will try their best to help every student find it. That there’s nothing to fear because every game is optional, worth questioning.

For me, I can unequivocally say that species counterpoint was the best, most useful thing I’ve ever studied. Those particular rules, though I followed them to a T, were beside the point. The point was microscopically tuning in that deeply to details at the intersection of melody and harmony, a false binary if there ever was one. And I don’t say that last part just because of my politics, or merely intellectually. I say it because of gnosis, direct experience. Because I took Michael Annicchiarico’s class seriously and it expanded my consciousness permanently.

(Occasionally a heavy musician will twig to what I’m up to. “Your music is about voice leading.” I could not possibly feel more seen. 💕)

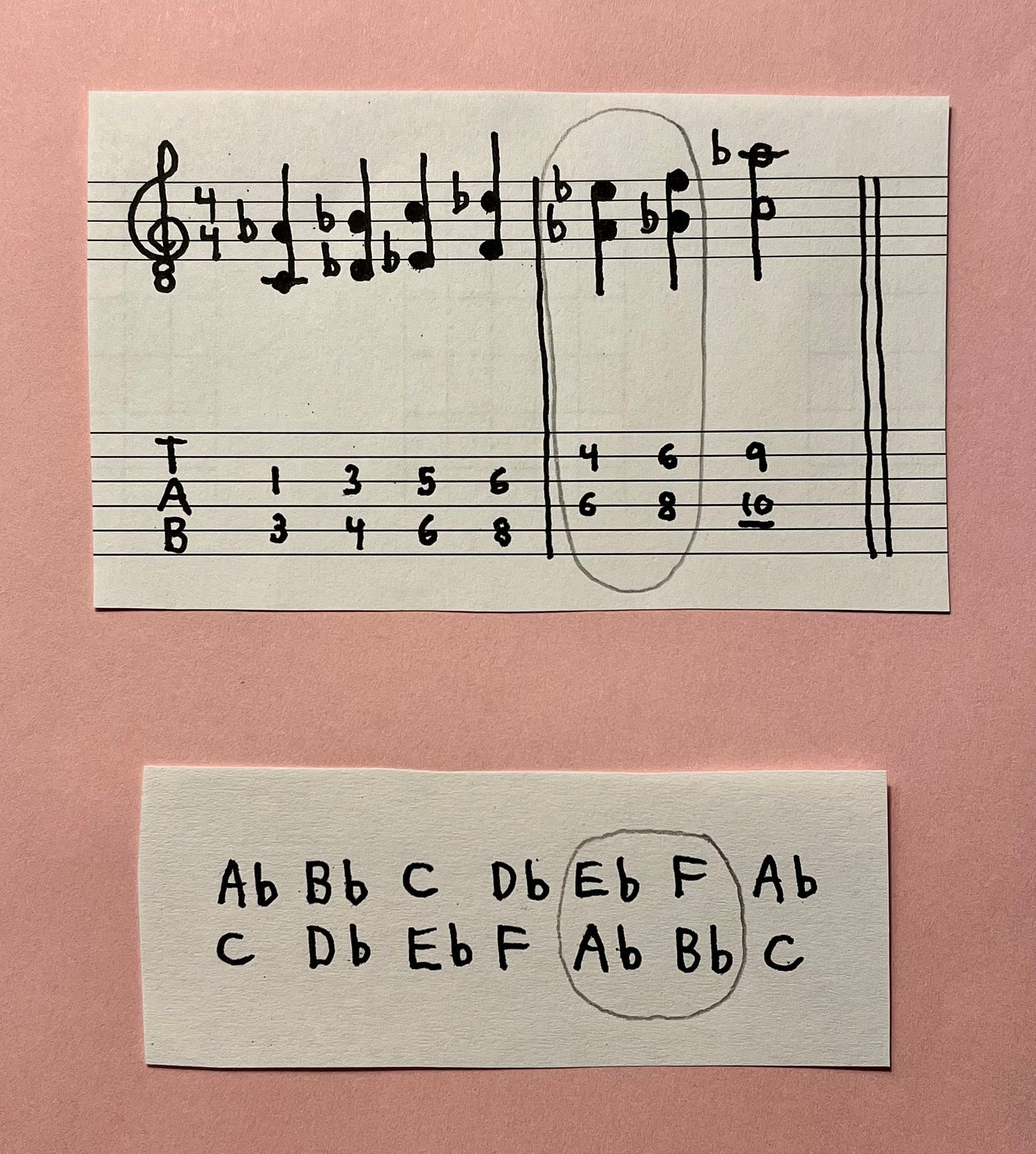

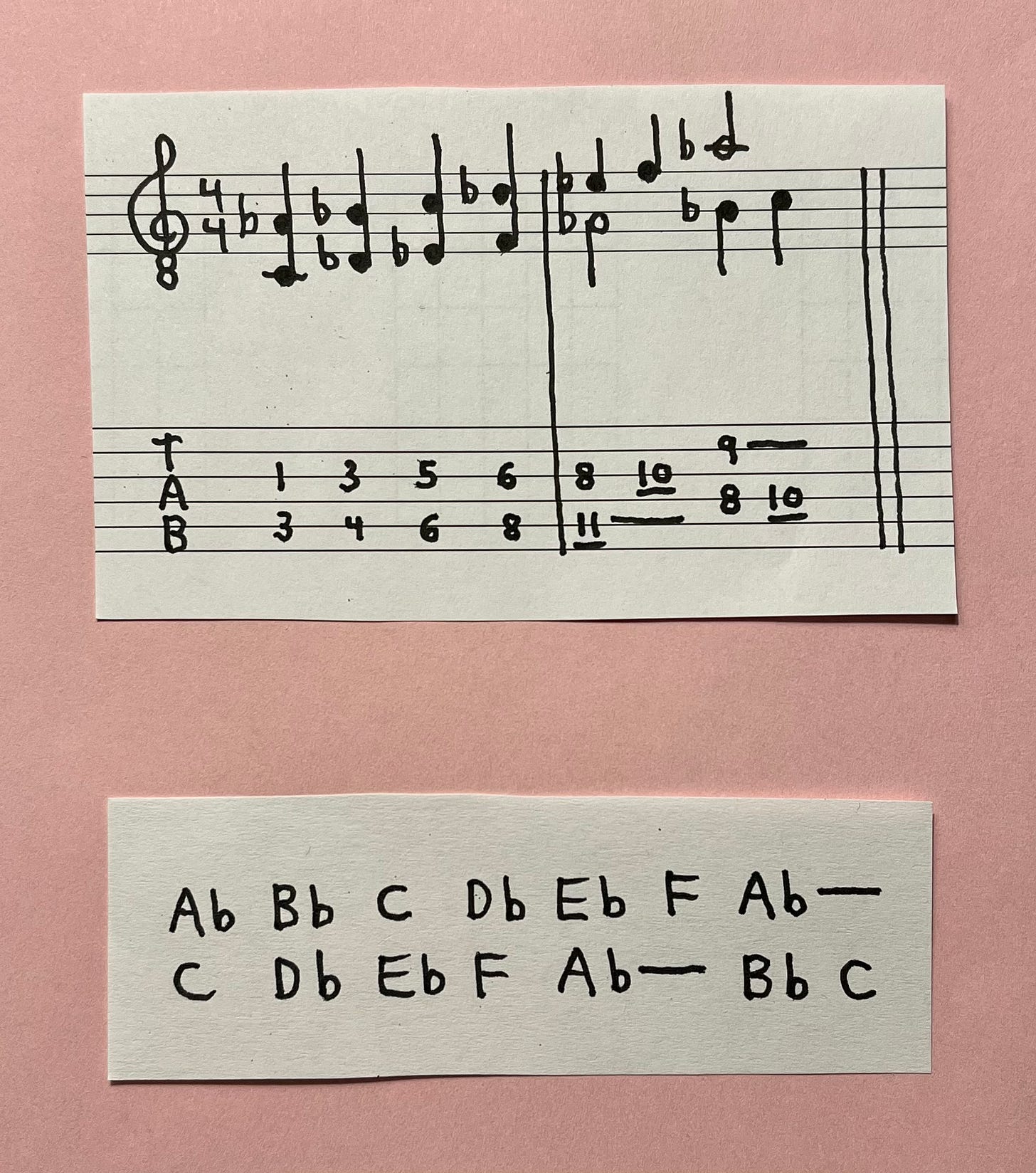

Like I said, I was surprised. It’s rare for parallel 5ths to sound bad to me. I’m not sure why I don’t like them here, but I’m happy I’m still paying attention, and I enjoyed the opportunity the problem presented. Here’s what I did to avoid them:

(It should be noted that I’m still breaking a rule of species counterpoint by approaching the fifth dyad the way I am. I remembered the principle but had forgotten the language until I looked it up. I’ve used a “direct 5th,” approached a perfect 5th by similar rather than contrary or oblique motion.)

(Guitarists may be interested in my left-hand fingerings. I play the first four dyads entirely with my index and ring, only plucking the first dyad, then sliding. For the fifth dyad, I stay with my index and ring. After plucking, I slide the index up a whole-step, approximating a pedal steel country sound. And now comes the interesting part, a new technique for me. I play the seventh dyad with my index and middle. After plucking, I slide my index up a whole-step, again for the pedal steel sound. But now I’ve pushed my index finger one fret higher than my middle finger, which is still holding down its note! I didn’t know you could do this, but apparently you can. 💕)