CW18

I don’t remember exactly when Otis Redding’s “(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay” went from hidden in plain sight to charged with significance for me—did I learn it for a student?—but I know that the night in October, 2004,* that I met Devendra Banhart (my brother’s band Feathers (without me sitting in; I was in the audience) opened for him, and Andy Cabic’s Vetiver, in Northampton, Massachusetts) I was showing him and everybody, back at my brother’s Grant Street apartment after the show, the chords on an acoustic guitar—especially the E(2) (DO, RE, MI, SO) manifesting in a functionally ambiguous way underneath the G major triad, the apparent tonic.

*I know when it was because I know it was during the first World Series the Boston Red Sox had won in eighty six years—an enormous deal in New England, even for those of us who didn’t usually follow sports. In fact, I’m almost certain the show was during (somehow!) the final game, making it 10/27/04.

(When I first started, around that time, meeting people I considered celebrities, I would rise up (as if to a challenge) and take up a lot of space. (That’s a charitable way of putting it.) E.g., my eagerness to share my new enthusiasm for “Dock of the Bay” to a captive audience of freak folk royalty—in my memory my presentation happens like two seconds into the hang.)

But the song is incredible. Allow me to show you what I’m focused on, and how it connects to new major.

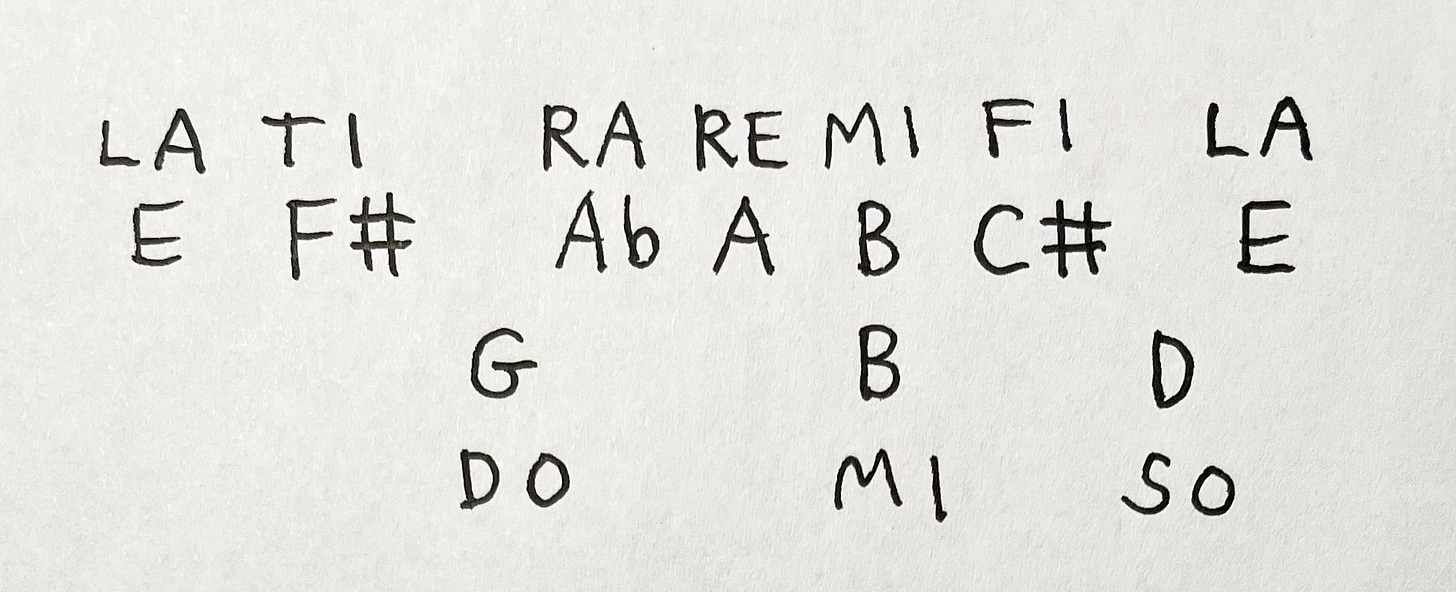

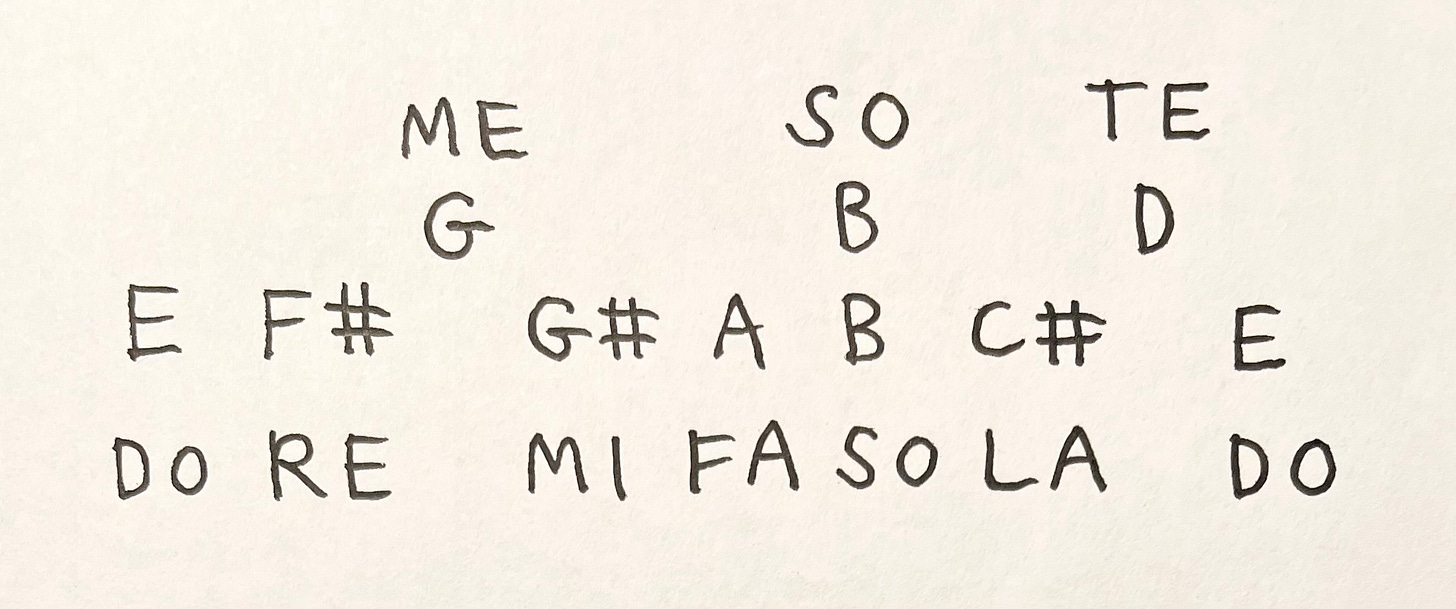

The best thing to do, before we begin, is go learn it: intro, verse, chorus, verse, chorus, bridge, verse, chorus, outro. It’s stranger than you might assume of a song this inevitable-seeming. You will need seven chords, all major: G, A, B, C, D, E, and F. However, do not neglect to incorporate some of Steve Cropper’s added tones, from his electric guitar part (he also co-wrote and produced the song), into your voicings. Each chord seems to carry the aura of its own major pentatonic scale (A chords in the verse are also sometimes decorated by an upper-neighbor FA, and the F in the bridge gets an upper-neighbor FI), but most important, in my opinion, is to add the F# to the first two of the three E chords in each chorus, and to put the G# on top of the B chord, from the second verse onward.

Sometimes when I’m improvising with new major over, say, a droning major triad

the major triad built off LA (LA, RA, MI) starts to take over, and the context flips.

The droning triad becomes a blues sound, hanging over gospel scale material that it’s grinding against. The former orientation, the new major way, still sounds alien to me—wild and fresh and sometimes challenging to make work. Conversely, the latter orientation is, for those of us familiar with American musics of the twentieth century, a mood of tension we are culturally acclimated to.

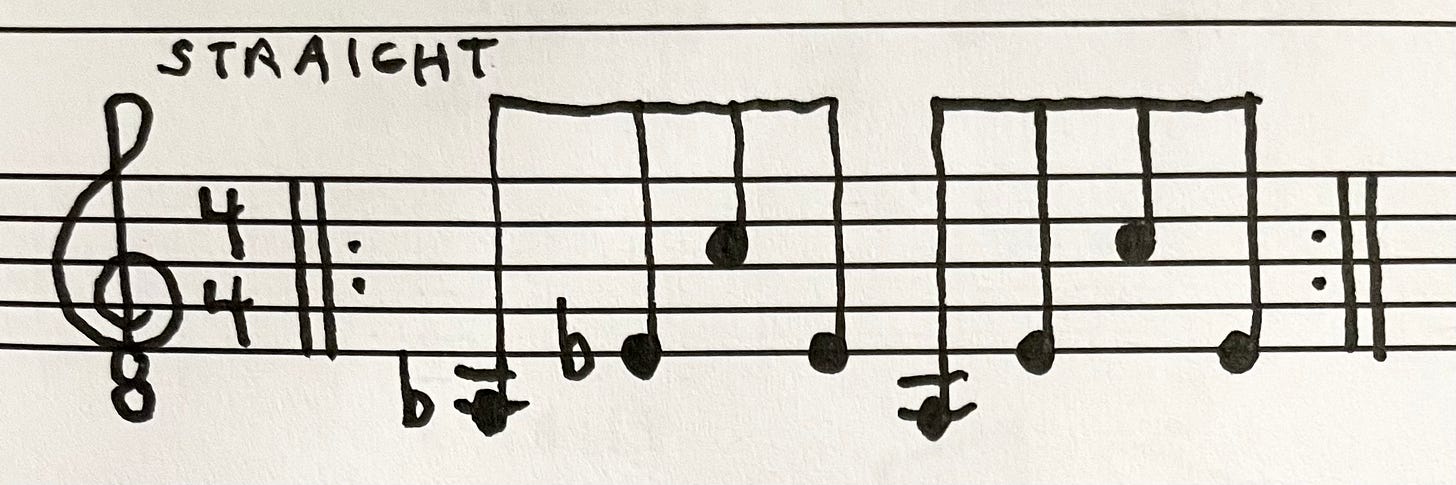

Imagine someone is playing this figure, an Ab major triad:

And now imagine someone comes in improvising this melody over it:

It sounds like blues.

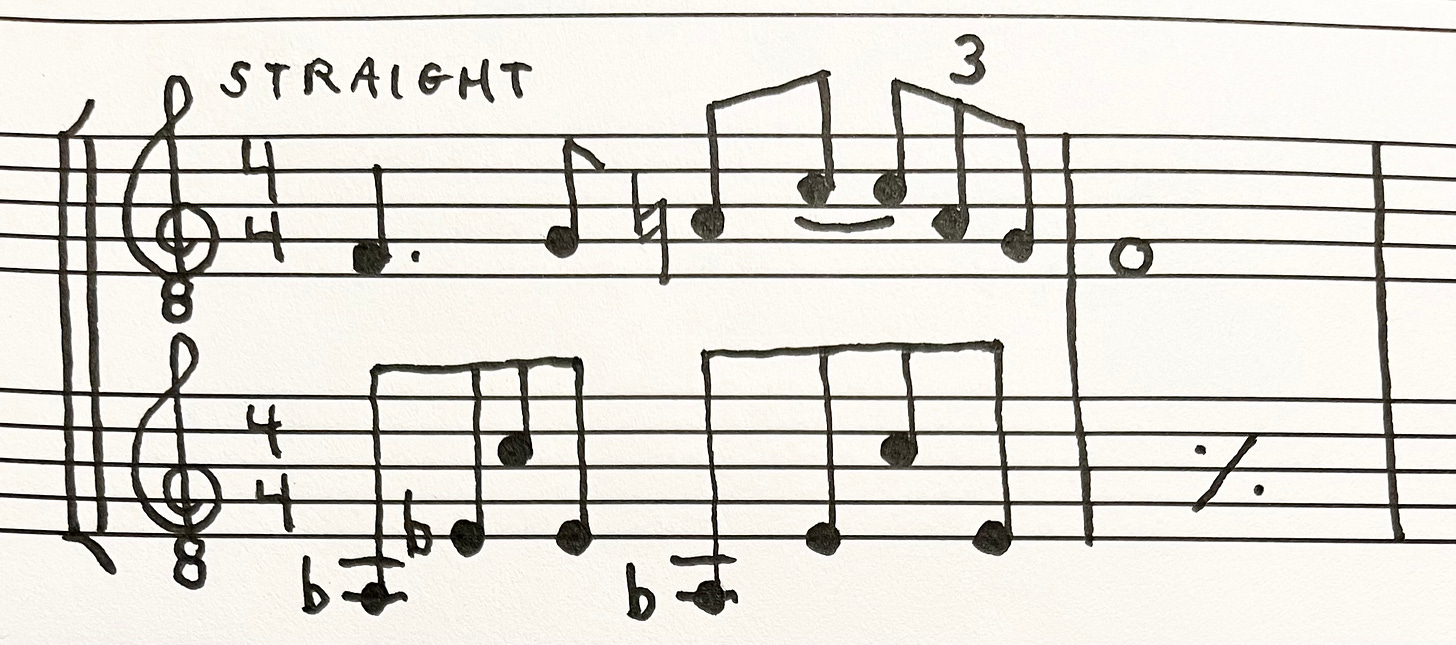

Okay, now imagine this same scenario, but the improvised melody is this instead:

The latter example is something from a Danilo Pérez interview on the Pablo Held Investigates podcast (10/3/22) (the interview is very incredible—go watch or listen if you haven’t). Pérez tells a story where he was playing the Ab chord, and Wayne Shorter came in playing the F, G, A, C tetrachord over it (under it?). Pérez was surprised enough to remember it—“I was like What?!”—and use it to illustrate a facet of Shorter’s genius: “He’s hearing these simple worlds that are coming together to create this complexity of sounds.”

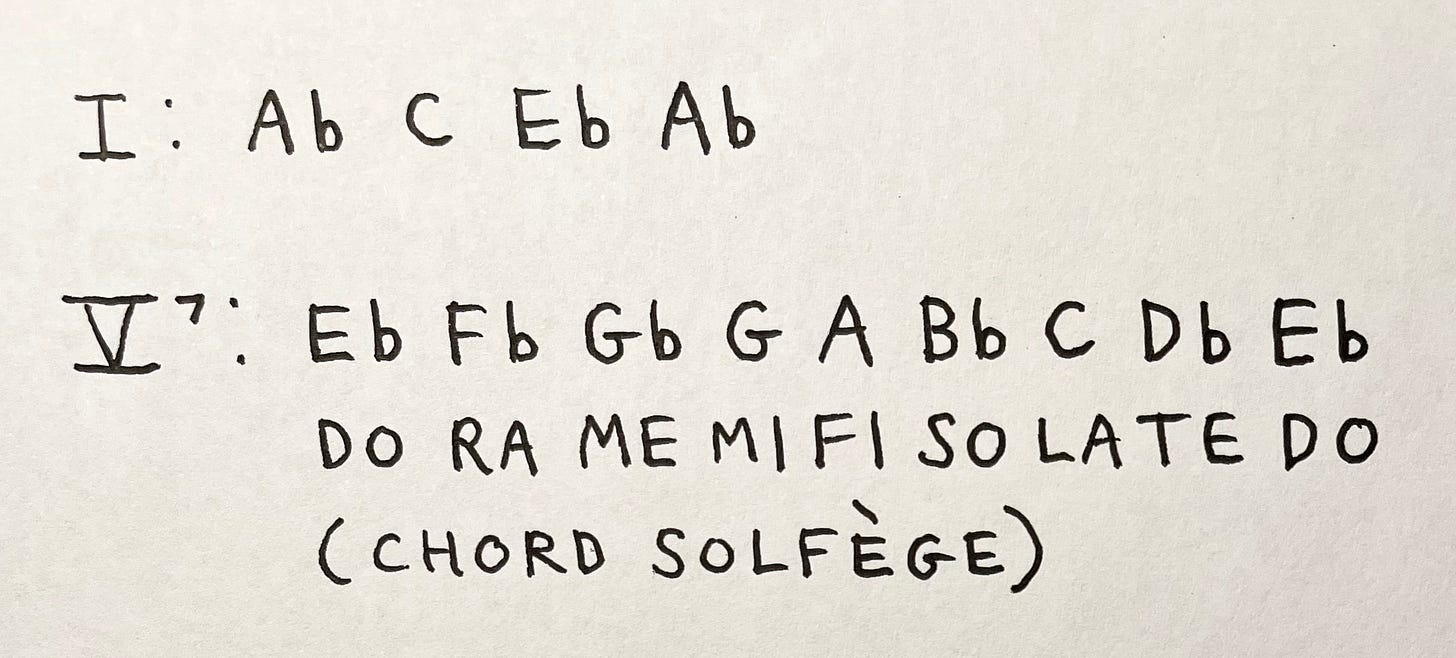

Pérez goes on to allude to a theoretical justification for what Shorter was hearing that’s familiar to me. The idea has to do with using a symmetrical diminished scale to pivot between four keys, spaced in minor thirds. Because they share a symmetrical diminished scale that they can use as a commonweal dominant, the four keys can begin to take on the sense of being equivalent, interchangeable. You can use Eb half-whole (symmetrical diminished) as the dominant of Ab.

This scale contains a complete Eb7 chord. But it also has a complete C7, A7, and F#7. You can look at the scale from any of these perspectives, and the seventh chord will always be filled in with the same tensions: RA, ME, FI, and LA. Picture it like a weird kaleidoscopic place with four identical doors you can leave out of, all leading back to a stable key center. None of them are favored; they all relate to the symmetrical diminished scale exactly the same way. So you may have entered from the Ab world, but you could just as well “return” to the F world, the D world, or the B world.

So when Shorter suddenly seems to be in F major (or at least DO, RE, MI, SO in F) against Ab major, the idea is basically that if he could’ve used Eb half-whole as a merry-go-round to get from one key to the other, why not just skip that step? He’s happy to overlay the two dimensions, to treat them as one place.

The only problem with this explanation, for me, is that it’s satisfactory. I’m not sure I even believe in such a thing as a correct or incorrect analysis—for me a theory is a song; what matters most is its beauty, its use—so I’m not about to say Pérez is wrong. (I love Danilo Pérez.) But I think we should always be careful that a powerful reading doesn’t eclipse the possibility of continuing to ask why. (Authorial intent remains a particularly virulent conversation ender. I guard against it always, including with myself! (I wonder what I’m really up to, but I’ll probably be the last to find out.))

Of course, when the interview came out—eighteen Octobers after the Feathers show—and I heard that music, it was fully uncanny. It was exactly the new major stuff I’d been practicing. But as much as I’d like to consider myself aligned with Wayne Shorter (R.I.P.) in any way—“He’s thinking of it like me!” or: “He invented new major and conveyed it to me psychically!—there’s a middle option. It isn’t symmetrical diminished, and it isn’t new major exactly. It’s “negative blues.”

To be continued…